For this tutorial we presume that you have completed the first tutorial, since it builds on the code produced from that.

Most of the time a web application will emit HTML. That's the fabric of which the web is made. Once in a while though, we might have to generate other types of responses. In these cases, we clearly don't want the output to get wrapped in the regular document rendering. For that we need an abnormal response. We have already seen one kind of abnormal response, with the k_PageNotFound, but this time we need a more specific kind. We'll extend the contact component with the capacity to render as a vcard.

To supply a ressource as a different content-type, we can use Konstrukts built-in support for content-negotiation, which is an often underutilised feature of the http protocol. To get this, we need to edit the "entity" component, so that the GET request can fork out to either the html or the vcard handler. We could do so manually in the GET() method, but there are generic hooks available for this purpose. After a revision of the component, we end up with this:

<?php class components_contacts_Entity extends k_Component { function renderHtml() { global $contacts; $contact = $contacts->fetchByName($this->name()); if (!$contact) { throw new k_PageNotFound(); } $this->document->setTitle($contact->full_name()); $t = new k_Template("templates/contacts-entity.tpl.php"); return $t->render($this, array('contact' => $contact)); } function renderVcard() { global $contacts; $contact = $contacts->fetchByName($this->name()); if (!$contact) { throw new k_PageNotFound(); } $t = new k_Template("templates/contacts-entity-vcard.tpl.php"); $response = new k_HttpResponse(200, $t->render($this, array('contact' => $contact))); $response->setContentType('text/x-vcard'); return $response; } }

As you can see, we now have two render-methods, instead of a single GET() method. The default GET() method will use these mappings to dispatch to one or the other, using content-type negotiation. There is a default mapping from content-type to renderer name, which you can find in the documentation.

Inside of the vcard renderer, we're creating an abnormal response. As discussed above, this circumvents the normal rendering pipeline and allows us fine grained control over the exact http response sent out.

Of course, we need the template to go with it in templates/contacts-entity-vcard.tpl.php:

BEGIN:VCARD VERSION:3.0 N:<?php echo $contact->first_name(); ?>;<?php echo $contact->last_name() . "\n"; ?> FN:<?php echo $contact->full_name() . "\n"; ?> EMAIL;TYPE=PREF,INTERNET:<?php echo $contact->email() . "\n"; ?> REV:<?php echo date("Y-m-dTH:i:sZ") . "\n"; ?> END:VCARD

Our component can now render in two different content-types, depending on the client's request. To see this in action, you can use the command line tool curl. Go to the command line and type:

curl --dump-header - --header "Accept: text/html" http://localhost/foo/www/contacts/jabba

You will get a dump of the HTTP response, as text/html. Now try requesting text/x-vcard:

curl --dump-header - --header "Accept: text/x-vcard" http://localhost/foo/www/contacts/jabba

As you can see, the same component now returns different representations, depending on the clients preference. This is in accordance with the HTTP protocol and some clients are capable of handling it just fine, but the most common clients - browsers - are generally not. Because of this, there is an alternative way. You can specify the content-type after the components name, separated by a dot (Actually, you should use the short name, rather than the full mimetype name). In this case, you can navigate to http://localhost/foo/www/contacts/jabba.vcard which will yield the same result as if you had requested the page with an accept header specifying that it wants text/x-vcard. Try it out with:

curl --dump-header - http://localhost/foo/www/contacts/jabba.vcard

Note that Konstrukt ignores the Accept header, when a short name is specified - The short name takes precedence. Thus, the following also gives a vcard:

curl --dump-header - --header "Accept: text/html" http://localhost/foo/www/contacts/jabba.vcard

As you may have noted above, there is some duplication between the two render functions. We can reduce this by moving part of it up into a more general handler on the component. In this case the top-level (dispatch()) would fit:

<?php class components_contacts_Entity extends k_Component { protected $contact; function dispatch() { global $contacts; $this->contact = $contacts->fetchByName($this->name()); if (!$this->contact) { throw new k_PageNotFound(); } return parent::dispatch(); } function renderHtml() { $this->document->setTitle($this->contact->full_name()); $t = new k_Template("templates/contacts-entity.tpl.php"); return $t->render($this, array('contact' => $this->contact)); } function renderVcard() { $t = new k_Template("templates/contacts-entity-vcard.tpl.php"); $response = new k_HttpResponse(200, $t->render($this, array('contact' => $this->contact))); $response->setContentType('text/x-vcard'); return $response; } }

This may also serve as an opportunity to use a powerful feature of Konstrukt, known as wrappers. Add the following snippet to /var/www/foo/lib/components/contacts/list.php:

<?php class components_contacts_List extends k_Component { ... function wrapHtml($content) { return ' <p><a href="' . htmlspecialchars($this->url()) . '">List contacts</a></p> <div id="content"> ' . $content . ' </div>'; } ... }

What this will do is that whenever a child component (Eg. components_contacts_Entity) is rendered, the response will be decorated. It will only apply for HTML responses, so our vcard response won't be affected. This provides a convenient way to place navigation and similar snippets of HTML, that relates to the location with in the url hierarchy.

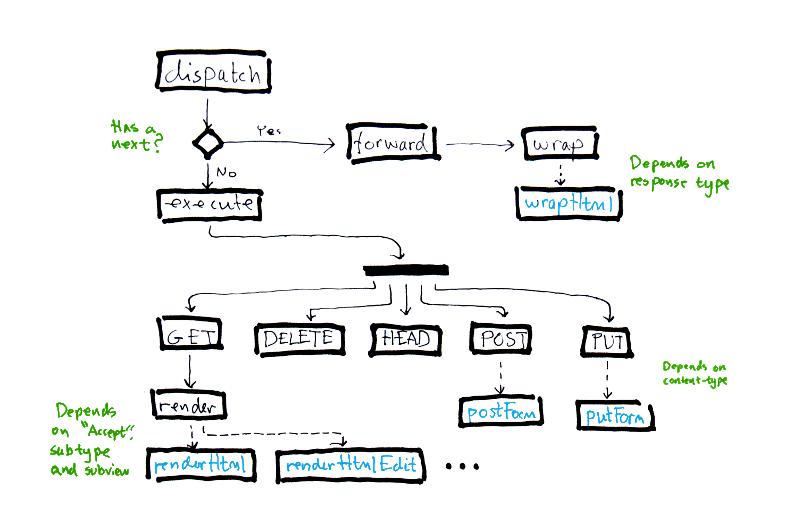

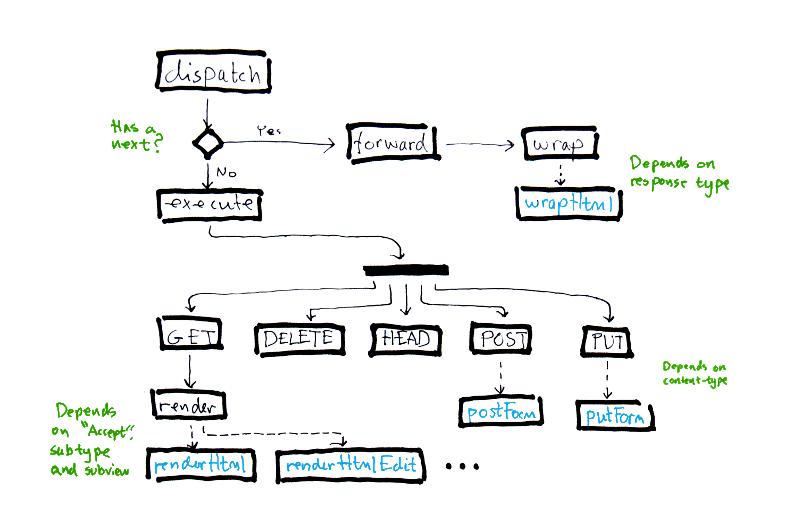

We have now introduced a number of concepts relating to the dispatch process. But to understand how they all fit together and what is really happening inside the library, we'll have to take a step back:

(You can skip this section, if your head is too full)

The diagram above depicts the process that a component goes through during execution.

A component starts its processing in the dispatch() method. This determines if there are any more components to dispatch to or if this is the last in the chain. In a nested path, each component will enter the dispatch() method and then delegate to the next, until the last segment of the path is reached.

If there is a next component, dispatch() uses first asks map() to translate the path segment into a component class name. It then calls forward(), which instantiates the component and delegates to it, starting the process over within the next component.

The last component in the chain will delegate to its own execute() method, instead of forward(). This will further delegate to a method that corresponds to the HTTP method, usually GET(). Finally, the GET() method calls render(), which will try to find a suitable renderer method to dispatch to, based on the requested content-type (Determined by Accept header or URL prefix) and - if applicable - subview.

When the forward() method dispatches to another component, it will receive a k_Response object. This is sent to the wrap() method. wrap() will check if there are any wrappers that match the content-type of the response. If so, it will pipe it through this to allow decoration of the response. Wrappers are very useful for rendering things like navigation. I you take a look at the root component (Located in /var/www/foo/lib/components/root.php), you will see that it has a method wrapHtml. Each time a sub component returns a HTML response, this method is used to decorate it. Since wrap() is only called upon a forward, the execute() method is further augmented to wrap the result of dispatch(). Thus, Root wraps itself for HTML responses.

All these methods may seem a bit much and it is probably the most complex part of Konstrukt. You don't need to understand the subtle differences to be able to use Konstrukt, but if you want to get the full benefit of the library there it is required knowledge. The point of having so many methods in the dispatch is that it gives different points to hook into, depending on what you intent. So it is very uncommon for any component to use all of these features at once. For starters, the way that render() and map() works are the most important.

Most web applications have to do with user input from html-forms. A component can implement a handler for any HTTP method - including the POST, which are closely related to forms. You can implement the POST() method on the component, to handle all POST requests, but just like you shouldn't implement GET() directly, but rather rely on render methods, you shouldn't implement POST() directly either. Instead, you can implement postForm() to accept the regular application/x-www-form-urlencoded type requests (The default encoding of a HTML form), or postMultipart() for multipart forms (Usually used with file uploads). If you want to support other input formats, the same rules applies - postXml() would accept a POST request with the Content-Type header set to text/xml. PUT type requests follow the same rules.

The payload of the request - usually fields of a form - can be accessed through the body() method. This corresponds to PHPs native $_POST superglobal, just like query() corresponds to $_GET. This naming is more correct, since the querystring is available in all requests - not just GET, and a payload can come with other types of request, such as PUT.

To continue from our running example, the first thing we need is to render a html form for editing a contact. A form can be seen as an alternate view over the resource. Konstrukt has the concept of sub-views to cater to this. Add the following to out 'entity' component:

<?php class components_contacts_Entity extends k_Component { function renderHtmlEdit() { $this->document->setTitle("Edit " . $this->contact->full_name()); $t = new k_Template("templates/contacts-entity-edit.tpl.php"); return new k_HtmlResponse($t->render($this, array('contact' => $this->contact))); } ...

And the template to go with it in templates/contacts-entity-edit.tpl.php:

<h2>Edit <?php e($contact->short_name()); ?></h2> <form method="post" action="<?php e(url('', array('edit'))); ?>"> <?php if (isset($contact->errors)): ?> <?php foreach ($contact->errors as $error): ?> <p style="color:red"> <?php e($error); ?> </p> <?php endforeach; ?> <?php endif; ?> <p> <label>First Name <input type="text" name="first_name" value="<?php e($contact->first_name()); ?>" /> </label> </p> <p> <label>Last Name <input type="text" name="last_name" value="<?php e($contact->last_name()); ?>" /> </label> </p> <p> <label>Email <input type="text" name="email" value="<?php e($contact->email()); ?>" /> </label> </p> <p> <input type="submit" /> </p> </form>

This is obviously a primitive way to render form components. HTML widgets are outside the scope of Konstrukt, but you can use third party libraries, such as Zend_Form to generate the html. If you use a real template engine, it may also provide a means for this.

To access the form, we need to add a link from the view page, so edit templates/contacts-entity.tpl.php:

<h2><?php e($contact->short_name()); ?></h2> <dl> <dt>First Name</dt> <dd><?php e($contact->first_name()); ?></dd> <dt>Last Name</dt> <dd><?php e($contact->last_name()); ?></dd> <dt>Email</dt> <dd><?php e($contact->email()); ?></dd> </dl> <p> <a href="<?php e(url('', array('edit'))); ?>">edit</a> </p>

You can now reach the form by clicking the url to contacts/jabba?edit. Internally, Konstrukt will translate this to renderHtmlEdit and dispatch to that method.

Now that we have the rendering of a form in place, we still need to process the POST request it will generate. Time to add some more methods to our component:

<?php class components_contacts_Entity extends k_Component { function postForm() { if ($this->process()) { return new k_SeeOther($this->url()); } return $this->render(); } function process() { global $contacts; $this->contact = new Contact( array( 'short_name' => $this->contact->short_name(), 'first_name' => $this->body("first_name"), 'last_name' => $this->body("last_name"), 'email' => $this->body("email"))); if (!$this->contact->first_name()) { @$this->contact->errors[] = "Missing first_name"; } if (!$this->contact->last_name()) { @$this->contact->errors[] = "Missing last_name"; } if (!$this->contact->email()) { @$this->contact->errors[] = "Missing email"; } if (!isset($this->contact->errors)) { try { $contacts->save($this->contact); } catch (Exception $ex) { @$this->contact->errors[] = $ex->getMessage(); return false; } return true; } return false; } ...

As this tutorial isn't about the model layer, the implementation of process() is kept simple. You can test a failure case by omitting one of the fields. Otherwise the entity is saved back to the database.

The postForm() method - while brief - deserves a few words on the way. If the processing goes well, we generate a redirect. In this case it's for the current components url. That will take the user back to the default representation after a successful operation. If there are failures, the form is instead redisplayed. Note that we have to explicitly call render() at the end. Without it, we would get a blank page.

This pattern is commonly known as "redirect after post" or "post-redirect-get" (PRG). Doing things in this exact way means that the users browser history won't store the POST actions, once the form has been completed. If we didn't do this, using the "back" button of the browser would try to re-submit the form. You have probably experienced this annoying behaviour on a web site more than once. Note that it is only after the form has been succesfully processed, that the redirect takes place.